PBA Galleries announces Sale 845: History of Science, Publishers’ Bindings from The Morris-Levin Collection, Miniature Books and Children’s Lit. Taking place on Thursday August 28, 2025 on offer is a smorgasbord of items including charts from the first celestial atlas printed to important milestones in the development of the theory of General Relativity. Also included are gorgeous illustrated publishers’ bindings, miniature books and maps disguised as jigsaw puzzles.

Of the 138 lots covering the history of science, 18 are devoted to Albert Einstein with 16 offprints (presented to the great man’s son Hans) on topics including aspects of General Relativity, early work on Unified Field Theory and the “Canal Rays” experiment (notorious because of colleague Emil Rupp’s contribution of falsified data). Especially notable is an unpublished autograph note to Nobel Prize winner Max von Laue on Einstein’s academic calling card. Interestingly, this may refer to the proposed Canal Rays experiment.

The seminal offprint of Einstein’s debate with Willem De Sitter on the shape of the universe is complemented with several inscribed early offprints by De Sitter concerning celestial mechanics as well as his 1934 On the Foundations of the Theory of Relativity, with Special Reference to the Theory of the Expanding Universe.

The book described by McLean in Victorian Book Design as “One of the oddest and most beautiful books of the whole century,” is also on the auction block; Oliver Byrne’s The First Six Books of the Elements of Euclid from 1847. It employs four-color printing as …more

Boston International Antiquarian Book Fair

The Boston International Antiquarian Book Fair (BIABF) will celebrate its 47th year at the Hynes Convention Center in Boston’s Back Bay, November 7-9, 2025. The annual fall event features pre-eminent international dealers offering the most sought-after collections of fine and rare books, maps, illustrations, and ephemera available on the global market. Sanctioned by the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America and the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, the fair’s specialties encompass art, design, music, science, medicine, literature, history, gastronomy, fashion, philosophy, and more.

More than 100 rare book dealers from Australia, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, Serbia, and 22 U.S. states will exhibit a treasure trove for seasoned bibliophiles and first-time attendees. Prices will range from the millions to the eminently affordable. Whether immaculately preserved or with the patina of age, each item will tell its own story. Booksellers hold a wealth of knowledge, both artistically and historically, about items in their collections. A complete list of exhibitors can be found at https://www.abaa.org/bostonbookfair/exhibitor-list1

Whether browsing or buying, the Fair will offer something for every taste and budget — books on art, science, fashion, politics, travel, cooking, sport, natural history, first editions, Americana, music, children’s books, and …more

Boston “Shadow Fair” Reports Strong Interest

MW Book Fairs, a collaboration between Duane A. Stevens of Wiggins Fine Books ABAA and Richard Mori of Richard Mori Books, has announced that dealer sign-ups for Books In Boston, the “shadow show”, have exceeded 40 dealers. This year’s fair is set for November 8 at the Hilton Boston Back Bay, with hours from 8 am to 4 pm. While dealer retention from last year is high, Richard and Duane are pleased to welcome several new dealers, including: Pico Banerjee, from Lewiston, Maine, the winner of the "shadow fair" half-booth auctioned off at this year's CABS conference. Also, Owl of Minerva, from West New York, NJ; Jason Phillips (Phillips and Phillips) from Rochester, NH; and Peter Forman (Custodians of History) from Plymouth, MA.

As in previous years MW has arranged for a room block at the Hilton, with a limited number discounted rooms available at $289 per night along with a discounted parking rate of only $30 per day and amenity fee waiver. As previously announced MW Book Fairs will again host breakfast one hour before fair opening in the Copley Room for all “shadow Fair” dealers and invited Hynes guests. The fair offers the advantage of …more

Select Rarities: Exceptional Books & Manuscripts

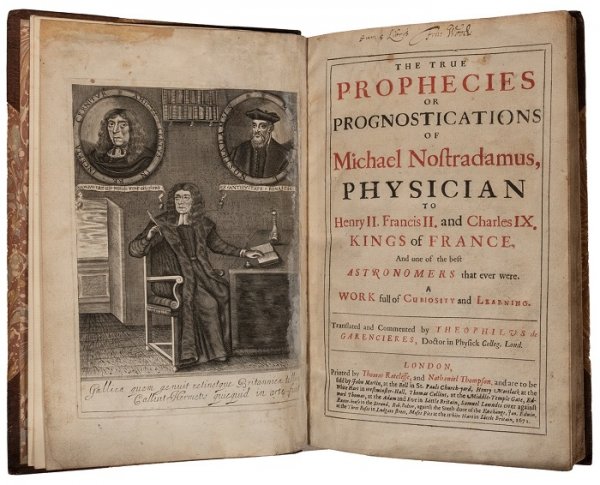

Absentee bidding for Potter & Potter's Select Rarities: Exceptional Books & Manuscripts auction are now being accepted, with reserve (minimum) bids noted. Live bidding begins on September 4th. For detailed descriptive cataloguing notes with illustrations of each lot, please click on the link and continue reading.

The Morgan Library & Museum will present Sing a New Song: The Psalms in Medieval Art and Life, the first exhibition of its kind devoted to the importance of the Psalms throughout medieval art, prayer, and everyday life. On view from

September 12, 2025, through January 4, 2026, Sing a New Song traces the impact of the Psalms on people in medieval Europe from the sixth to the sixteenth century, encompassing daily practices and performance, as well as the creation and illumination of Psalters (Books of Psalms). Drawing on five years of scholarly research, the exhibition and accompanying publication take the Psalms out of their established place in religious texts and paint a vibrant picture of the people who used them — men, women, and children — both religious and lay. Psalms are some of the most beloved texts in the Abrahamic traditions of the three monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. These sacred poems constitute the longest and most popular book in the Bible. They include expressions of lament and loss, petitions and confessions, as well as exclamations of joy and thanksgiving — universal themes that speak to what it means to be human. Included in this show are the varieties of books that aided in these devotions — Psalters, Breviaries, Missals, and Graduals, among others — some of which were exquisitely illuminated. The exhibition explores how the Psalms were used, both at church and at home; how they were illuminated; how they were performed; and how they appear at both the beginning and the end of life.

In the manuscript traditions of many cultures across Europe, North Africa, and West Asia, more copies of the Book of Psalms survive than any other type of text. The prayer book known as the Book of Hours was based on the Psalms and was a best-seller among laypeople in the fifteenth century. Through translations into Latin and the vernacular, the Psalms permeated the intellectual culture of medieval Europe. Children used Psalters to learn to read, patrons commissioned versions in their native languages, and theologians authored the most influential interpretive writings of the Middle Ages around the Psalms.

More than any other text, the Psalms informed the language of the liturgy, and the Psalter served effectively as the prayer book of the church. Priests, monks, and nuns were required to pray all 150 psalms weekly. Laypeople across Europe, imitating these practices, fueled a demand for Psalters. The exhibition highlights Psalters across varying cultures, including an extremely rare Hebrew Psalter from a Jewish community in Tuscany as well as one of the very first printed Hebrew Bibles. Psalms were also performed or sung by monks, clergy, and laypeople, using books such as Psalters, Breviaries, Antiphonaries, and Books of Hours, which were often commissioned by the wealthy and sumptuously illuminated. Women found new ways to engage with books thanks to the proliferation of texts in everyday languages. Wealthy women were known to commission their own Psalters and Books of Hours for personal use, as seen in the celebrated “Hours of Catherine of Cleves,” commissioned by the Duchess of Guelders in 1440.

The exhibition concludes with a moving example of the use of psalms as solace, seen through the Prayer Book of Sir Thomas More. Heavily annotated by the future saint, who kept it with him while incarcerated in the Tower of London in the months before his execution, the Prayer Book shaped More’s faith, inspired his writings, and offered him comfort. Additional highlights of the exhibition include a Winchester Bible leaf (England, ca. 1160–80) from the Morgan’s collection; Isaac ben Ovadiah’s “Books of Truth” (Psalms, Job, Proverbs); the Scenes from the Life of Saint Augustine of Hippo altarpiece, on loan from the Met Cloisters; and exemplary loans from the New York Public Library, including the “Tickhill Psalter.”

For more information contact Daniela Stigh at (212) 590-0310 or dstigh@themorgan.org.

Book Fair Calendar (Updated 7/ 18/2025)

Tennessee Book & Ephemera Fair. Franklin, TN. July 25–27, 2025.

PulpFest. Mars, PA. August 7–10, 2025.

Rocky Mountain Book & Paper Fair. Castle Rock, CO. August 15–16, 2025. (more information)

PBFA Book Fair. Edinburgh, Scotland. September 6, 2025.

Rochester Antiquarian Book Fair. Rochester, NY. September 6, 2025. (more information)

York National Book Fair. York, England. September 12–13, 2025.

Empire State Rare Book & Print Fair. New York, NY. September 26–28, 2025.

Allentown Paper Show. Allentown, PA. October 4–5, 2025.

(read more)...

by Thomas HuckansBeyond Oppenheimer: Every Scientist a Modern Prometheus

The story told about the birth of the atomic age in Los Alamos is, at best, one of zealous overconfidence in progress and misguided dreams of global peace. At worst, it is a story of abdication of responsibility and callous indifference. Regardless of the frame of discourse, the common perception is that scientists were on a hamster wheel, unable to get off until seeing the bomb’s completion through, as depicted strikingly in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. However, not everyone stayed.

Joseph Rotblat, a Polish and British physicist whose work on fast neutron fission earned him the “privilege” of working at Los Alamos, was the most famous deserter of the Manhattan Project. He had only agreed to develop the bomb for fear that Hitler might acquire nuclear weapons. When General Leslie Groves let slip the purpose of the bomb was to “subdue the Soviets,” Rotblat seriously began to question his role at Los Alamos. Shortly afterward, upon learning that the Nazis had abandoned their nuclear program, Rotblat left the Manhattan Project, although not without the government attempting to paint him as a Soviet informant.

Rotblat’s story highlights the choice all weapons-research scientists can and should make. He identified three reasons why other conscientious physicists stayed: (1) “pure and simple” scientific curiosity; (2) trying to save American lives, coupled with the resolution to ensure the bomb would never again be used after the war; and (3) worrying about their careers. But according to Rotblat, those with a “social conscience” were a minority—most were content with others deciding how to use their research. In war, most people’s mindsets hardened, and the unthinkable during peacetime became a matter of course. But Rotblat was not the only physicist from the Manhattan Project to reject the atomic bomb. For example, Leo Szilard drafted the Szilard petition, advocating for the bomb to be demonstrated rather than detonated in an attack on a city, and I.I. Rabi, who refused to join the Manhattan Project, dedicated much of his life to promoting peace and the limitation of nuclear weapons. However, the US government was largely indifferent to their efforts, at least in part due to a lack of a unified front... (continue reading)

The Morgan Library & Museum will present A Lively Mind: Jane Austen at 250, a major exhibition devoted to the life and legacy of the beloved literary icon. On view from June 6 through September 14, 2025, A Lively Mind immerses viewers in the inspiring story of Jane Austen’s authorship and her gradual rise to international fame. Iconic artifacts from Jane Austen’s House in Chawton, England,  will join manuscripts, books, and artworks from the Morgan, as well as from a dozen other institutional and private collections, to present compelling new perspectives on Austen’s literary achievement, her personal style, and her global legacy.

will join manuscripts, books, and artworks from the Morgan, as well as from a dozen other institutional and private collections, to present compelling new perspectives on Austen’s literary achievement, her personal style, and her global legacy.

“Jane Austen has inspired generations of readers, and the Morgan is honored to join the celebrations marking the 250th anniversary of her birth,” said Colin B. Bailey, Katharine J. Rayner Director of the Morgan Library & Museum. “Bringing together the Morgan’s expansive collection of Austen works, particularly her letters, alongside many exquisite loans, A Lively Mind is a rare opportunity to experience Austen’s many facets at once, from her family life to her authorship and her legacy.”

Born on December 16, 1775, Austen began cultivating her imaginative powers and her ambition to publish during her teen years. Austen’s upbringing was unconventional, particularly in the degree of familial support she received for her creative endeavors. Her creativity found expression in a range of artistic pursuits, from music making to a delight in fashion. Writing with an intimate knowledge of women’s lives but removed from many of the gender expectations herself, Austen gave voice to the everyday experiences and emotions of English gentlewomen.

Drawing significantly on Austen’s correspondence with Cassandra, her sister and lifelong confidante, A Lively Mind allows a picture of Austen’s life to emerge through her own words. Contemporary prints and drawings evoke sights familiar to her, while first-edition copies of her six major novels, from Sense and Sensibility to Persuasion, demonstrate how her identity as author was concealed from her earliest readers.

“A Lively Mind examines how it was possible for Austen to publish her now-beloved novels when women …more

Julia Margaret Cameron at the Morgan

An exhibition featuring the work of Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the most Important and innovative photographers of the nineteenth century, opens on May 30, 2025.

The Morgan Library & Museum will present Arresting Beauty: Julia Margaret Cameron, a major exhibition exploring the revolutionary work of one of photography’s most pioneering and influential figures. On view from May 30 through September 14, 2025,  it brings together a remarkable selection of Cameron’s evocative portraits and staged compositions, offering a rare glimpse into the artistic vision of a woman who transformed photography into an expressive art form. Organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), London, the exhibition features works drawn from the V&A’s extensive holdings of nearly one thousand of Cameron’s photographs, which comprise the largest and most comprehensive collection of her work in the world. Arresting Beauty includes an array of Cameron’s most striking works, including her celebrated portraits of preeminent Victorians, allegorical tableaux, and a selection of her subjects inspired by literature and biblical themes. Also on view are pages from Cameron’s unfinished memoir, Annals of My Glass House.

it brings together a remarkable selection of Cameron’s evocative portraits and staged compositions, offering a rare glimpse into the artistic vision of a woman who transformed photography into an expressive art form. Organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), London, the exhibition features works drawn from the V&A’s extensive holdings of nearly one thousand of Cameron’s photographs, which comprise the largest and most comprehensive collection of her work in the world. Arresting Beauty includes an array of Cameron’s most striking works, including her celebrated portraits of preeminent Victorians, allegorical tableaux, and a selection of her subjects inspired by literature and biblical themes. Also on view are pages from Cameron’s unfinished memoir, Annals of My Glass House.

Colin B. Bailey, Katharine J. Rayner Director of the Morgan, said, “We invite the public to discover the daring and poetic world of Julia Margaret Cameron. This exhibition offers an opportunity to witness the artistry of a woman who redefined photography and secured its place among the fine arts.”

“Julia Margaret Cameron was a pioneer in photography,” said Joel Smith, the Morgan’s Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography. “At a time when photographers were expected to do little more than find an attractive vantage point and make a correct exposure, she wielded her camera as an instrument of imagination and emotion. Arresting Beauty is a showcase for Cameron’s gaze—one that saw photography not as an exercise in accuracy, but as a pursuit of feeling.”

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) was born in Calcutta (modern-day Kolkata) to a French mother and an English father. In 1848, with her husband and children, she moved to England, where her sisters introduced her to the elite cultural circles in which they traveled. Residing in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight, where she was close neighbors with the poet Alfred Tennyson, Cameron acquired her first camera at age 48. In only eleven years, she would create thousands of exposures and leave an enduringimage of the Victorian era as an age of intellectual and spiritual ambition. “I longed to arrest all beauty that came before me,” Cameron once declared, “and at length the longing has been satisfied.”

Cameron’s prodigious drive helped her become a probing portraitist of leading writers, artists, and scientists such as Tennyson, Thomas Carlyle, George Frederic Watts, and Charles Darwin, while her absorption in fine art, notably Renaissance painting, led her to create staged tableaux in a mode that has been perpetually rediscovered by photographers down to the present. Most distinct of all was Cameron’s wholly personal handling of her medium. Heedless of contemporary conventions of technique, alert to the happy effects of accident, and indifferent to critical scorn, she embraced a style of spontaneous intimacy that distanced her from the photographic establishment of her time and class. Motion blur, highly selective focus, and even fingerprints on the glass negatives (which required developing before their emulsions dried) are among the idiosyncrasies of her singular oeuvre.

Cameron was quick to exploit publishing and promotional opportunities: At London’s South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum [or V&A]), she secured not only an exhibition in 1865 but also …more

Hindman’s Printed and Manuscript Americana Auction

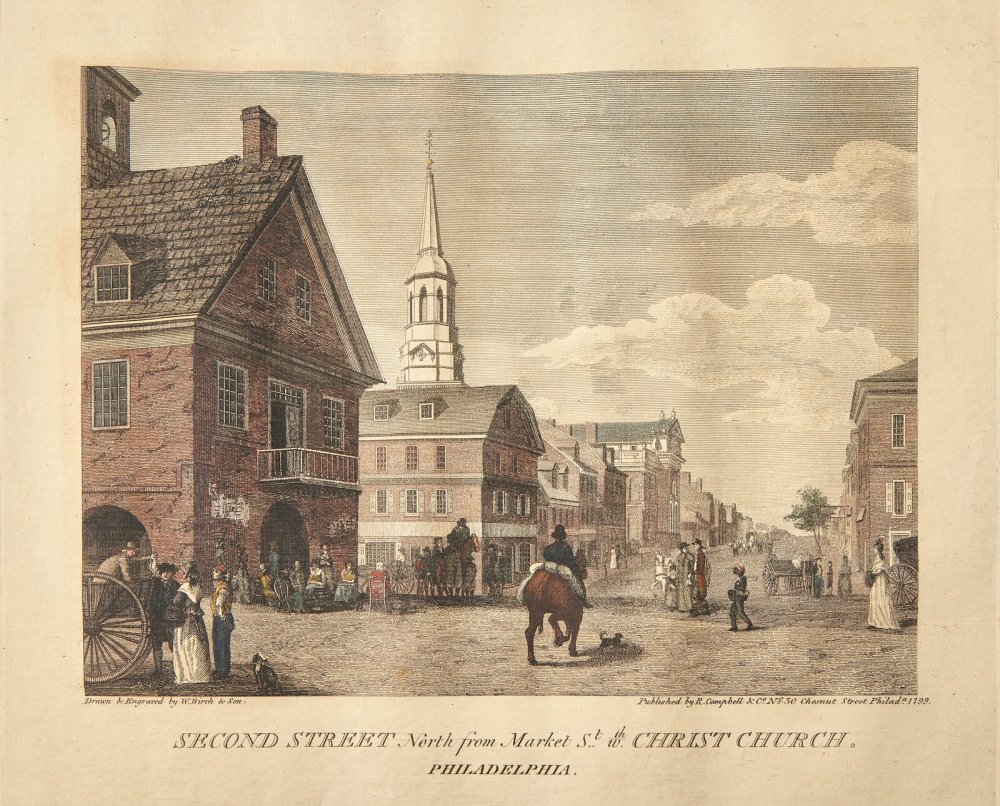

Freeman’s | Hindman’s Printed and Manuscript Americana auction on January 29 delivered extraordinary results, achieving nearly $1.2 million more than double the pre-sale estimates. Held in Philadelphia following a preview during the firm’s inaugural Americana Week exhibition in New York, the auction saw an impressive 188% sell-through rate by value, with 89% of lots successfully sold.

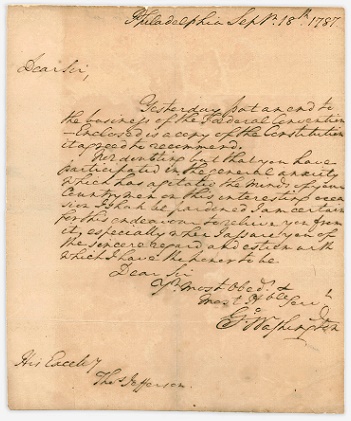

The results underscore the strong demand for rare Americana, led by an exceptional selection of Presidential material. The auction’s top lot, a printed broadside of George Washington’s first Inaugural address (Lot 56),  shattered expectations, soaring past the $15,000–25,000 estimate to achieve $381,500. While newspaper printings of Washington’s address are relatively common, broadside editions are exceptionally rare&ndsh;the Providence printing is one of two known surviving copies, with the other housed at The Henry Ford Museum.

shattered expectations, soaring past the $15,000–25,000 estimate to achieve $381,500. While newspaper printings of Washington’s address are relatively common, broadside editions are exceptionally rare&ndsh;the Providence printing is one of two known surviving copies, with the other housed at The Henry Ford Museum.

Other highlights included a first edition of The Federalist (Lot 32), authored by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, which fetched $127,500 against the $60,000–90,000 estimate. Additionally, a Rare Broadside of Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural address (Lot 39), printed in the mid-19th century, realized $19,200, surpassing its $5,000–8,000 estimate. Only two other examples of this printing have ever appeared at auction, with another copy held at the Library of Congress.

Materials from three landmark expeditions to the American West–led by acclaimed photographer Joseph K. Dixon and funded by philanthropist Rodman Wanamaker to document the lives and cultures of Native American communities–drew remarkable attention during the sale. Notably, Dixon’s original diary from the Second Wanamaker Expedition (Lot 48) achieved an impressive $54,400, far surpassing the pre-sale estimate of $6,000–9,000. While Dixon’s Original Typed Manuscript for “The Vanishing Race” (Lot 49) was estimated at $3,000 – 5,000 and sold for …more

by Anthony MarshallOh Jerusalem! (originally published December 2001)

Notes from the Antipodes

I recently bought a good collection of books to do with calligraphy. A very good collection, to tell the truth, the property of a former President of the Australian Society of Calligraphers. As I browsed amongst them, marveling at the skill of calligraphers and at the beauty of manuscripts, a passage in the introduction of one them caught my eye. “A good calligrapher must have the qualities of a warrior: he must plan ahead carefully but when he goes into action, he must be bold and decisive.” Or words to that effect.

Luckily for calligraphers, when they make a mess of things, the only thing spilled is ink. Warriors get to spill blood. Sometimes the enemy’s, but often their own. Small boys seldom think of this, when they dream of being knights in shining armor. I know I didn’t. As a boy, I sometimes dreamed of being a crusader, of riding with Richard the Lion-Heart and helping him deliver Jerusalem the Golden from the infidel hordes. After our successful venture, he would dub me knight, touching me with his sword on each shoulder as I knelt before him. “Arise, Sir Anthony.” I would journey home in triumph, clutching a splinter of the Holy Cross or the Holy Rood or the Holy Something, and spend the rest of my days delivering damsels in distress, slaying dragons and performing similar useful deeds of chivalry. (Before I went off to join the U.S. Cavalry, that is, to have fun shooting up Apaches.

That was during my “Boots and Saddles” phase.) No doubt many English boys of my generation – and for generations before me – had similar fantasies. How could we not? Chivalry was in our blood. Our national patron saint was St. George. We were the direct descendants of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table; we were steeped in the myths of Camelot. And Jerusalem – as any English boy knew – was really a part of England. It had simply been misplaced. So when we sang William Blake’s “Jerusalem” we knew the answer to the poet’s rhetorical question “And was Jerusalem builded here?” Of course it was. Right here, “ In England’s green and pleasant land.” I even knew where. Our English Jerusalem nestled in a fold of the Sussex Downs, on the coast, midway between Worthing and Brighton . What’s more, when I was eleven years old I became a Boy Scout. Each shoulder of my scout shirt sported a white label embroidered with blue lettering: “The Bishop of Jerusalem’s Own Scouts.” That felt pretty special. We were not merely the Bishop’s scouts, we were his Own Scouts. Like the King’s Own Light Infantry. Or the Queen’s Own Hussars. When we went to scout camps and jamborees, other scouts – the First Worthings, say, or the Fifth Brightons – would peer at our shoulders and wonder. Jerusalem? Were we foreigners? No, we came from Windlesham House School, actually. But the Bishop of Jerusalem (whoever he was) had picked us specially. The Pope had the Swiss Guard to look after him; the Bishop (wherever he was) had us.

To tell the truth, it was all very confusing. In geography we learned that the capital of Israel was not Jerusalem but Tel Aviv. But when you looked at the pretty colored maps at the back of your bible, you couldn’t find Tel Aviv. You could find Jerusalem all right but it wasn’t in Israel it was in “Palestine” or “The Holy Land” or “Judaea” or …continue reading

Fine Printed Books & Important Americana at Auction

Freeman’s | Hindman’s Fine Printed Books and Manuscripts, Including Americana auction on November 14 delivered an impressive total of $1.85 million far surpassing pre-sale expectations. Featuring standout collections of printed Americana and natural history manuscripts, the auction achieved a remarkable sell-through rate by value of 145%, with 92% of lots successfully sold. The Federalist (NY, 1788) was the top lot of the day, demonstrating the enduring demand for important Americana.

Gretchen Hause, Senior Vice President and Head of the Books and Manuscripts Department, Chicago, stated: “The extraordinary success of this auction not only exceeded our expectations but also underscored the continuing strength of the rare book and manuscript market. The remarkable sale result for The Federalist, which far surpassed its estimate,  reflects the enduring significance of the foundational works that shaped democracy in the United States. Similarly, the demand for superlative copies of beloved literary works remains very strong, with prices realized far surpassing their estimates, demonstrating that the timeless appeal of literary works continues to inspire and resonate with collectors. Very strong interest in some of the most renowned works of natural history rounded out the sale and contributed to the exceptional result.”

reflects the enduring significance of the foundational works that shaped democracy in the United States. Similarly, the demand for superlative copies of beloved literary works remains very strong, with prices realized far surpassing their estimates, demonstrating that the timeless appeal of literary works continues to inspire and resonate with collectors. Very strong interest in some of the most renowned works of natural history rounded out the sale and contributed to the exceptional result.”

Written primarily by Alexander Hamilton, with significant contributions from John Jay and James Madison, The Federalist essays (Lot 299) were instrumental in swaying public opinion during the ratification of the United States Constitution. Freeman’s | Hindman’s auction featured a highly coveted thick-paper presentation copy, believed to have been owned by Captain David Olmstead, a Revolutionary War veteran who served at West Point and the Battle of Ridgefield. This exceptionally rare edition—one of only seven to come to auction in the past 50 years—sparked enthusiastic bidding, ultimately selling for $203,200, more than triple the pre-sale estimate.

The sale also featured an extraordinary selection of ornithological and natural history works, highlighted by eight John Gould monographs from a distinguished private collection. The standout was Gould’s A Monograph of the Trochilidae, or Family of Humming-Birds (Lot 234), which exceeded its high estimate, closing at $88,900. William Lewin’s The Birds of Great-Britain with their Eggs (Lot 243) from the same collection captured significant interest, realizing $41,275—four times the pre-sale low estimate.

Other highlights from the natural history category included: Gould, John. The Birds of Europe. London, 1837, the first edition, which sold for $63,500; Gould's A Monograph of the Ramphastidae...Toucans. London, [1852-] 1854, the second edition, which brought $47,625; Audubon's The Birds of America. NY, [1839-] 1840-1844, the first octavo edition, fetched $44,450 and a first edition of Sibthorpe's Flora Graeca. London, 1806-1813 sold for $21,590

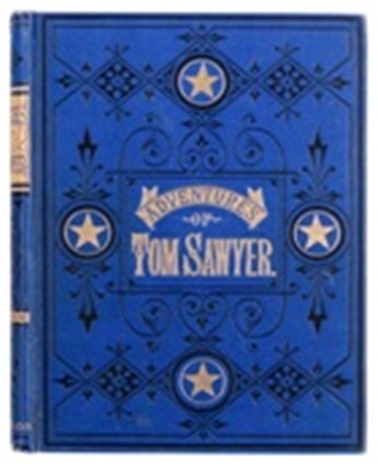

Two remarkable literary treasures from the Library of Dr. John Talbot Gernon captivated collectors at the Freeman’s | Hindman’s auction. The first issue of the American edition of Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera (1911), featuring an exceptionally rare original dust jacket, soared to $20,320, well above the pre-sale estimate of $6,000–8,000. This marked only the second time this particular dust jacket variant—depicting Christine staggering and swooning—has ever appeared at auction. Meanwhile, a desirable copy of Samuel L. Clemens’ (“Mark Twain”) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer attracted intense bidding, ultimately realizing $41,275, significantly exceeding its pre-sale estimate of $4,000–6,000. Also, a first edition of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) in a remarkably well-preserved dust jacket fetched $22,860, drawing enthusiastic interest from bidders.

Other notable auction highlights included Vancouver's A Voyage of Discovery... London, 1798, first edition with the atlas, which sold for $22,860; Mathew's Pencil Sketches of Montana. NY, 1868. the first edition which fetched $53,975; and McKenney and Hall's History of the Indian Tribes of North America... Phila., 1836-1844. in the first edition which fetched $44,450

For more information and complete sales results call (872) 270-3103.

by John C. Huckans2024 Election Season Ends... for now

Many would agree that the 2024 election season has been the weirdest in years – not only because Trump, Harris and Walz are candidates that keep satirists in business, but because future historians will look back and record that 2024 may be the year it became painfully obvious to almost everyone that it was also when most major media companies dropped all pretense of objectivity and professionalism, giving full-throated support to a public/private partnership with one of our major political parties in the information distribution business – to which point I'm certain the ABC-sponsored debate was the first time I witnessed a candidate having to take on three people in what was advertised as a one-on-one contest.

Politically-motivated attacks calling candidates either fascist or communist are not only not helpful because accusations of that sort are lacking in historical context, but miss the mark by revealing absence of understanding of what those terms mean.

Old Soviet-style communism, surviving in part in such places as Cuba and Venezuela, eliminated private ownership of industry and agriculture, putting party apparatchiks in charge of running nearly all segments of the economy. Whether or not this was a good idea can be answered by observing the standard of living and morale of people who have lived under the system for a long time.

National socialism (fascism) is a system of private/public partnerships where most ownership of the means of production, both agricultural, industrial, and the service economy (including education and distribution of information through the traditional press and electronic media) remains in private hands but under the strict scrutiny and control of the state. For the purpose of this discussion “the state” is defined as the dictatorship of the unelected, whether an individual or an autonomous and unaccountable “administrative state”.

"At any rate, Germany was a pioneer in de-emphasizing the importance of the individual in favor of enshrining group identity"

In Germany during the 1930s, the Third Reich had close business alliances with favored companies such as Bayer/IG Farben, (manufacturers of Zyklon B gas); Hugo Boss (makers of uniforms for the SS, Hitler Youth, the Wehrmacht, and in recent years clothing for fashionistas everywhere) and others. Thomas Watson and IBM, pioneers in the new data processing industry, spent time in Germany advising the Third Reich on best ways to use the technology to more minutely analyze and catagorize the nation's population, especially according to age, sex, mental ability, religion, ethnic backgound and other characteristics. Officially dividing people by ethnicity would in later years be enthusiastically encouraged by political activists and made part of public policy in the United States. At any rate, Germany was a pioneer in de-emphasizing the importance of the individual in favor of enshrining group identity – while at the same time demonizing or scape-goating the group least favored by the state. I leave it to the reader to guess which group that is in the U.S. at the present time.

The similarities between fascism and one of our major political parties are many – both seek and depend on control of the media and dissemination of information to the public in order to promote the party's agenda. The National Socialists in Germany organized the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda directed by Joseph Goebbels – in the United States of the present day, ABC/Disney, NBC, MSNBC, CBS, CNN, NPR & PBS do much the same – protestations to the contrary notwithstanding. One of the interesting things about the current political establishment's neo-fascist ambitions, is that its agenda is being marketed ingeniously by much of the media to the more gullible elements of society as being somehow virtuous. I suppose party faithful marching in the streets of Berlin during the 1930s also thought they were virtue-signalling.

Although much has been written and said about Biden/Harris as less than ideal heads of state because of their demonstrated ineptitude in formulating or carrying out sound public policy (i.e. the economy, mismanagement of the border by design and executive order, propensity to involve the nation in foreign wars, apologists for crime, etc.), a good case can be made that they have been excellent place holders for their party – enamored enough by the trappings of the office to be willing to take orders from the unseen dictatorship of the unelected. Proponents of one party rule will definitely vote accordingly.

New Work by Chopin Discovered at the Morgan

Curator Dr. Robinson McClellan uncovered a previously unknown waltz written in the hand of composer Frédéric Chopin in The Morgan Library & Museum’s collection. The discovery of an unknown work by Chopin has not happened since the late 1930s. The Morgan’s manuscript consists of twenty-four notated measures that the composer asks the pianist to repeat once in their entirety.

Chopin famously wrote in “small forms,” but this work, lasting about one minute, is shorter than any other waltz by him and is

nevertheless a complete piece, showing the kind of “tightness” that we expect from a finished work by the composer. The beginning of the piece is most remarkable: several moody, dissonant measures culminate in a loud outburst, before a melancholy melody begins.

None of his known waltzes start this way, making this one even more intriguing. The manuscript is only slightly larger than an index card (102 x 130 mm, about 4 x 5 inches); based on other similarly-sized manuscripts by Chopin, it is assumed that it was meant as a gift for inclusion in someone’s autograph album. Chopin usually signed manuscripts that were gifts, but this one is unsigned suggesting that he changed his mind and withheld it.

The Morgan’s Associate Curator of Music Manuscripts and Printed Music, Robinson McClellan, first came across the manuscript in 2024 when he began cataloging the Arthur Satz Collection, which came to the Morgan earlier that year; he found it peculiar that he could not think of any waltzes by Chopin that matched the measures on the page. McClellan called upon leading Chopin expert Professor Jeffrey Kallberg of the University of Pennsylvania to work with him to verify the manuscript’s authenticity and to understand the role of the work in Chopin’s musical life.

Extensive research points to the strong likelihood that the piece is by Chopin. McClellan and Kallberg also enlisted the help of external experts on Chopin as well as the Morgan’s paper conservators, who confirmed that the paper and ink are consistent with what Chopin customarily used. These investigations all point in one direction: this is a …more

by Brendan SherarLetter from Asheville

Dear friends, colleagues, and fellow BIBLIOphiles,

As many of you may know, BIBLIO's headquarters is in Asheville, NC - an area recently devastated by Hurricane Helene. Thankfully, BIBLIO remains fully operational and has experienced no disruption in service throughout the disaster and its aftermath.

But two-thirds of our staff live and work in the area, and while we're also thankful to report that we and our loved ones are safe and have suffered only some manageable property damage, that is not the case for many thousands of families and individuals here in Western North Carolina.

There remains an enormous amount of work to deliver essential food, water, supplies, and basic services to our region. We are grateful to the tens of thousands of relief workers who are here helping us to locate and rescue missing or stranded people, restore access to basic services, and deliver food, water, and supplies to our communities. Equally so, we are grateful for the generous donations of critical supplies and financial support pouring in from around the U.S. While we may be one small city in the Appalachian mountains, we are clearly part of a greater community of generosity and compassion.

It will be weeks before all critical infrastructure and services are fully restored and many months - if not years - to rebuild communities, neighborhoods, businesses, and livelihoods that have been literally destroyed by this disaster. For an area that relies on 13 million visitors a year drawn here for its stunning natural beauty and unique mountain culture, the effects of this disaster will be long and far-reaching.

BIBLIO has been a part of Western North Carolina since its beginning. Many of our staff - myself included - have grown up in the Asheville area. Several of us have children who have also grown up here. A number of BIBLIO's booksellers - including some of its first clients - are located here. We are committed to doing our part to provide relief and assistance to our neighbors and to help rebuild our beautiful city and surrounding area.

This is where you come in: I would like to ask you to join us in supporting organizations that are literally working around the clock to supply desperately-needed relief to our communities. When you make a purchase on BIBLIO, please choose the roundup option, which directly benefits "BeLoved Asheville", a local and 100% volunteer-staffed non-profit that is distributing water, food, and other essential supplies to tens of thousands of people daily.

I'd also like to encourage you to make direct contributions to "BeLoved" or any of other organizations working tirelessly to deliver aid to where it's needed the most.

From myself, my staff, and the communities of Asheville and Western North Carolina, I want to thank you for your generosity and for keeping us in your thoughts and prayers. It truly takes a village, and we are ever-grateful that you are all part of ours.

With gratitude,

Brendan Sherar

Founder & CEO of BIBLIO

Doings at the Morgan - Franz Kafka Exhibition

The Morgan Library & Museum presents Franz Kafka, on view November 22, 2024, through April 13, 2025, marking the 100th anniversary of the author’s death. The exhibition celebrates Kafka’s achievements, creativity, and continued influence on new literary, theatrical, and artistic creations around the world. Franz Kafka is presented in collaboration with the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford, whose extraordinary Kafka holdings will appear in the United States for the first time. The items on view include literary manuscripts, correspondence, diaries, and photographs, including the original manuscript of his novella The Metamorphosis.

When Franz Kafka died of tuberculosis at the age of forty, in 1924, few could have predicted the influence his relatively small body of work would have on every realm of thought and creative endeavor over the course of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Kafka’s novels and short stories have had an immense influence on literature, art, and culture in the United States in particular, and visitors to the Morgan will be able to examine important items from the Bodleian’s Kafka archive in the place where his work has made an outsize impact. The exhibition not only sets Kafka in the context of his times but also shows how his own experiences fueled his imagination, taking visitors on a journey through his life and influences—from his relationship with his family and the people closest to him to the places where he lived and worked, through to his last years of illness and …more

The Morgan Library & Museum announces its 2024-2025 concert season of Music at the Morgan that celebrates the intersection of art, literature, and music with engaging concerts inspired by its collections and exhibitions.

This year, to celebrate the exhibition Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy, soprano Candice Hoyes will perform works ranging from opera to jazz that highlight aspects of Greene’s life and work. Skylark Vocal Ensemble with narrator Christine Baranski will perform a musical rendition of Charles Dickens’ classic A Christmas Carol, while the original manuscript is on view in the historic library. The Morgan will also present two composers in focus, diving deep into the creative processes of composers Philip Glass and Fanny Mendelssohn, with performances accompanied by lectures and films, respectively.

Early music concerts feature Boston Early Music Festival Vocal & Chamber Ensembles’s concert version of Georg Philipp Telemann’s Don Quichotte; and Francesco Corti offers an evening of Harpsichord Suites featuring works by George Frideric Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach. The Paris-based Modigliani Quartet presents a repertoire of Romantic and twentieth century music; the season showcases a new

generation of musicians through partnerships with the George and Nora London Foundation for Singers and Young Concert Artists.

For more information contact Christina Ludgood at (212) 590-0312 or Chie Xu(212) 590-0311.

Freeman | Hindman June Sales Results

On June 6 in Chicago, Freeman’s | Hindman presented Fine Literature from the Collection of Richard C. McKenzie, which was met with tremendous enthusiasm from the market. Bidders vied for first editions and literary high spots of the 19th and 20th centuries with all 297 lots selling, of which nearly 60% sold for prices surpassing presale estimates. The collection drew international bidders, nearly 30% of whom were bidding with Freeman’s | Hindman for the very first time.

The collection included fine copies of high spots of American and English literature from the last two centuries with works by Jane Austen (1775-1817), Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), William Faulkner (1897-1962), F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1944), and Herman Melville (1819-1891) headlining the sale.

Highlights from the collection included: Emily Dickinson. Poems, Poems Second Series, and Poems Third Series. First editions, which

sold for $22,860; Herman Melville. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. First American Edition, selling for $22,860; and F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Beautiful and Damned. First edition, first printing, which brought $16,510.

The top lot of the month came from the June 25 Books and Manuscripts auction in Philadelphia, where a rare portolan chart of the Mediterranean by Joan Oliva sold for $152,400, more than seven times the presale estimate. Oliva was the most prolific and highly regarded member of the distinguished Oliva family, a mapmaking dynasty that …more

by John C. HuckansTogether We Thrive - Divided Not So Much

I think Voltaire was right. If people weren't able to lose themselves in their gardens or books, the world would surely go mad. And some days I think it already has. The last few years have not been happy ones for the republic for many reasons, not the least of which seems to be the officially-encouraged policy of divisiveness and inter-group hostility, carried out by a partnership of well-financed private advocacy groups and one of our major political parties. At the lowest level, morally bankrupt politicians will beat the drums for war when the tide of public opinion turns, and some voters will support them if they're told the nation is under military threat. In scenarios where a dangerous situation is caused or exacerbated by the elected leaders themselves, it might be called war in the national interest.

The “military/industrial complex” is much larger than it was in Eisenhower's time and I suspect there will never be a true accounting of the many hundreds of billions of dollars spent supplying arms to warring peoples in various parts of the world – most recently in Ukraine and Israel. Also, well-placed economic and political elites stand to make a lot of money in the nasty but lucrative side hustle of influence peddling, but when these actions and feckless policies lead to armed conflict, some of the bravest of the “elites” will express the willingness to fight, if necessary, to the last combatant – usually someone else's son or daughter and preferably from a working class background. …more

by John C. HuckansThe Iron Cage, a Review

(originally published May 2014)

The literature of the Nakba (expulsion and dispossession of the Palestinian people, starting on or about May 15, 1948) is vast. There are many published personal narratives such as Sari Nusseibeh’s Once Upon a Country (NY, Farrar, Straus, 2007) and Karl Sabbagh’s Palestine, A Personal History (NY, Grove Press, 2007), unsparing historical accounts such as expatriate Israeli historian Ilan Pappé’s The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford, OneWorld, 2006), and countless books and essays focusing on various aspects of the struggle. There is even a significant sub-genre of literature relating to the “Israel Lobby” by such writers as ex-Congressman Paul Findley and more recently by academics John Mearsheimer (University of Chicago) and Stephen Walt (Harvard).

With this as a backdrop, it’s refreshing to read a book that places the Palestinian experience within a broader context. …more

by John C. HuckansA Book Club of One

Note: The baying of the hounds from both sides of the aisle is a reminder that the quadrenniel political season is well under way, and what better excuse to reprint our review of Ray Ginger's biography of Eugene Debs, the labor reformer, socialist and ultimately crusading populist and pacifist who was convicted and sent to jail for his public speech.

*

The oldest book club I remember was the “Book-of-the-Month” club. My parents subscribed, which is how I first was introduced to Winston Churchill's 6 volume memoirs of World War II. Each volume, as published, may have been offered as a bonus to new members.

And while in boarding school in Connecticut, a faculty member promoted something called the “Book Find Club” where students interested in history, economics and philosophy could order new books from BFC catalogues at prices which seemed ridiculously low even at that time. Like a starving person at a Chinese buffet, I usually bought more than I could read before the next catalogue arrived.

One I remember reading almost immediately (biography refracted through the lenses of history, economics and philosophy) was Robert L. Heilbroner's The Worldly Philosophers. It was an expanded version of his PhD. dissertation and apparently was so successful that it was revised and reprinted several times. It is still widely offered on the internet by online sellers: “The Worldly Philosophers is a beautiful novel written by the famous author Robert L. Heilbroner. The book is perfect for those who wants to read philosophy, history books. The main character of the story are John Maynard Keynes, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Thomas Robert Malthus, Thorstein Veblen” [sic]. Seriously, I kid you not.

At any rate, book clubs have proliferated over the years. Television personalities publicized eponymous ones, promoting books, often of the “as-told-to” genre, and almost immediately day time television watchers would order them on Amazon or head to the nearest Costco. There are also local book clubs that meet in libraries or in each others homes, where members take turns making selections. And at the height of the Pride & Prejudice craze some years ago, Book Source Magazine helped to publicize a “Jane Austen” book club – as I recall it ran out of steam after Northanger Abbey or Mansfield Park. With the demise of traditional bookstores, many of which stocked backlist titles on their shelves for years, of necessity the trend has been toward self-publishing or what used to be called “vanity press” publication. At its most embarrassing it can involve being invited to a gathering to hear an author speak about his or her book, while feeling the pressure to buy autographed copies at the conclusion of the talk. Rare unsigned copies of anything seem to be at a premium of late.

While some book clubs promote the idea of thousands of people reading the same book at the same time – I find myself more intrigued by the notion that sometimes I might be the only person on the planet reading whatever it is I'm reading at the time. Right now that book is …more

Hindman, to Merge with America's Oldest Auction House, Freeman’s

Today, the pioneering, full-service auction house Hindman announces that it will continue to expand its national footprint by merging with venerable, 200-year-old Philadelphia-based Freeman’s. With a combined six salerooms and 18 regional offices across the country, Freeman’s and Hindman stand to have the largest, coast-to-coast presence of any auction house in the United States, with plans to expand into international markets. The union of these two preeminent businesses represents the foundation of a dynamic and comprehensive company well- positioned to lead the upper-middle auction market. Under the name Freeman’s | Hindman, the company is combining their robust digital infrastructures into a singular website and highly targeted online initiatives.

As one of the first actions, Freeman’s | Hindman will be opening its new permanent New York saleroom in January 2024. Located at 32 East 67th Street in the heart of the Upper East Side’s art district with up to 5,000 square feet of space available to the company, it is truly setting its sights on New York as a major center of growth. For Freeman’s, it is a return to the city with a physical presence, although both companies have had senior specialists working with clients in New York for many years. This move is in response to the strong demand they have established in this vibrant and key area of the art market.

“I’m truly excited to bring together these two esteemed auction houses under one roof,” asserts Executive Chairman, Jay Frederick Krehbiel. “The merger strengthens our advantage in an increasingly competitive auction market and sets us up for continued growth across the United States and globally, especially with Freeman’s existing international relationship with Lyon & Turnbull.”

Driven by a client-first approach, dedication to excellence, and innovative strategy, the two houses are natural partners. As America’s oldest auction house, Freeman’s adds more than two centuries of achieving market-setting results to Hindman’s 40-year record of realizing stellar prices while providing outstanding service, particularly to trusts and estates professionals nationwide. A strength also lies in both firms’ specialist teams, whose profound knowledge and unrivaled expertise span all …more

Outstanding Results at Potter & Potter Auctions Magicana Sale

Potter & Potter Auctions' December 9th sale had a 99.3% sell through rate, with prices noted including the company's 20% buyer's premium.

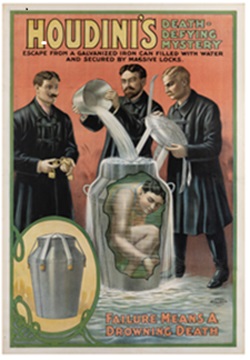

The top lot in this sale was Harry Houdini's (Erik Weisz) Death-Defying Mystery. Estimated at $40,000 - 60,000, it brought $180,000 - three times the high estimate. The linen backed rarity, one of perhaps five extant, measured 40" x 30”  and was published in Cincinnati & New York by Russell-Morgan Litho. in 1908. The one sheet color lithograph depicted Houdini in his Milk Can escape, crouched down inside the metal container with water pouring down over his body. The poster, acquired at the Houdini Estate Sale held in New Jersey in 1981 by a former owner, was removed from one of many trunks found in the basement of Houdini’s home at 278 West 113th Street in Harlem, where it had been stored in the decades following the magician’s death.

and was published in Cincinnati & New York by Russell-Morgan Litho. in 1908. The one sheet color lithograph depicted Houdini in his Milk Can escape, crouched down inside the metal container with water pouring down over his body. The poster, acquired at the Houdini Estate Sale held in New Jersey in 1981 by a former owner, was removed from one of many trunks found in the basement of Houdini’s home at 278 West 113th Street in Harlem, where it had been stored in the decades following the magician’s death.

Thurston (Kellar’s Successor) - Invested with the Mantle of Magic, was estimated at $15,000-25,000 and realized $48,000. The half-sheet lithograph promoting magician Howard Thurston was published in Cincinnati by The Strobridge Litho. Co. in 1908. Measuring 30" x 20” and depicting Thurston and fellow magician Harry Kellar side-by-side, with Mephistopheles looking on at the historic scene on the stage of Ford’s Theatre in Baltimore, when Thurston was presented with Kellar’s “mantle” of magic.

A collection of Suzy Wandas' (Jeanne Van Dyk) performing apparatus, estimated at $5,000-8,000, sold for $38,400. The case held virtually all of the props used by Wandas for the act she presented in variety theaters around the world. These include pails, holders, metal stands, a vanishing cane and an appearing cane; palming coins; multiplying billiard balls, her make-up bag and makeup; silks and flags; dummy cigarettes and gimmicked matchboxes; a breakaway fan; playing cards; and many others. According to Potter's experts, this was "a remarkable time capsule of one of the few female performers to excel as a variety artist in the twentieth century as a magician – not to mention as part of a family act, on circus, and as a musician, on two sides of the Atlantic."

Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin's Quadrille Mignonette des Soirées Fantastiques de Robert-Houdin, estimated at $1,000-2,000, fetched $28,800. This book of …more

Results of Hindman's Recent Fine Books & Manuscripts Auctions

A complete copy of Edward S. Curtis’s seminal The North American Indian, arguably the most complete ethnographic record of the native peoples of North America ever assembled, stole the show in two days of Fine Books & Manuscript auctions at Hindman on November 9 and 10. The Curtis was the top lot of the single-owner Fine Books from the Dorros Family Collection auction on November 9, which saw a sales total of $1.5 million. Combined with the various-owner Fine Printed Books & Manuscripts, including Americana auction on the following day, the Chicago auction house achieved $2.4 million during the back-to-back sales.

Documenting one of the great races of mankind Curtis’s The North American Indian was one of the most ambitious and expensive publication projects of its kind, taking more than two decades to complete and resulting in one of the most important published works of the 20th century. All told, The North American Indian comprises 40 volumes: 20 text volumes featuring 1,511 illustrations, 1,505 photogravures, four maps and two diagrams, along with 20 supplemental folio volumes featuring some 723 full sheet photogravures in sepia, many of which have become iconic images. Funded in part by JP Morgan, Curtis set out to document as much of Native American culture and history as he could. Writing in the introduction, he explained that “the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost.” Complete sets in any condition are rare on the market and therefore highly coveted, and the set offered from the Dorros Family Collection auction attracted enthusiastic bidding that sent the piece past its low estimate selling for $882,000 to …more

Ricky Jay Collection Part II Fetches Nearly $518,000

Potter & Potter's remarkable event, featuring ephemera, correspondence and artifacts from the collection of the late actor, sleight-of-hand magician and noted author Ricky Jay, realized $518,000.

The 323 lot auction held on October 28, 2023 had a sell-through rate of 98% with an average lot value of $1,600. All prices noted include the auction house's 20% buyer's premium

The top lot in this sale was an archive of correspondence between Karl Germain (b. Charles Mattmueller, 1878–1959) and his assistant, student, successor, and friend, Paul Fleming. This collection of written materials from 1908 to 1959, estimated at $30,000-60,000, brought $66,000. A highlight of this grouping was a note from Germain explaining the construction, packing, and details of his one-man Spirit Cabinet, a routine he developed after his Chautauqua and Lyceum heyday, the secret of which was not revealed in the books authored by Stuart Cramer that chronicle Germain’s life and magic.

Karl Germain (b. Charles Mattmueller, 1878–1959) and his assistant, student, successor, and friend, Paul Fleming. This collection of written materials from 1908 to 1959, estimated at $30,000-60,000, brought $66,000. A highlight of this grouping was a note from Germain explaining the construction, packing, and details of his one-man Spirit Cabinet, a routine he developed after his Chautauqua and Lyceum heyday, the secret of which was not revealed in the books authored by Stuart Cramer that chronicle Germain’s life and magic.

Three scrapbooks and other materials chronicling London's Bartholomew Fair and its popular entertainment, estimated at $8,000-12,000, realized $27,600. They were compiled in the 19th century and included more than 400 pages of notes, broadsides, engraved portraits, book extracts, news clippings, letters, and related memorabilia chronicling the August celebration held annually from 1833 -1855.

Three Shows In One. The World Famous Houdini, Master Mystifier, was estimated at $5,000-10,000 and fetched $14,400. The oversized white, black, and orange linen backed broadside was printed in 1925 and was decorated with Houdini’s bust portrait, bats, and a witch. It was made to promote Houdini’s final tour, which ended unexpectedly with his hospitalization after sustaining a blow to the …more

Potter & Potter's Antarctic Expedition Sale Realizes $630,000

Potter & Potter Auctions has announced the results of the 430 lot sale held on October 12, 2023. The auction had an average lot value of nearly $1,500 and prices noted include the auction house's 20% buyer's premium.

The top lot in this sale, the original 35mm motion picture camera used to film parts of Richard E. Byrds' first Antarctic expedition, estimated at $30,000-50,000, made $40,000. The footage produced from the camera would go on to be used for the film “With Byrd at the South Pole,” issued in 1930.

The camera was used between 1928-30 by Paramount Publix Corporation cinematographers Willard Van der Veer and Joseph T. Rucker, the first professional cinematographers in Antarctica who also won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography, the first documentary to win an Oscar.

Other outstanding lots in the sale included Ernest H. Shackleton's The Heart of the Antarctic, Being the Story of the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-1909 and The Antarctic Book. Winter Quarters 1907-1909, estimated at $20,000-30,000 and which sold for …more

A Season of Book Auctions at Swann

Books and manuscripts had a standout winter/spring season at Swann Galleries. “As a company whose origins are as a book auction house, it is reaffirming to see this growth, over 25%, in our book department over the last year. Even more exciting is that the results reflect not only strength in our established departments but also great momentum in our latest  specialized sale, Focus on Women,” noted President Nicholas D. Lowry.

specialized sale, Focus on Women,” noted President Nicholas D. Lowry.

The top auctions of the season included two record-breakers in their respective categories: Printed & Manuscript African Americana and Early Printed Books. Both sales recorded their highest totals in history at the house. African Americana earned $1,378,838 on March 30, and the timed online auction of Early Printed Books closed on May 4 at $1,326,560.

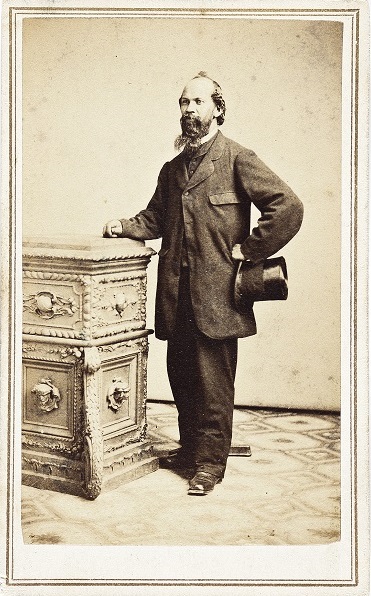

Highlighted sales included an inscribed carte-de-visite portrait of early photographer James Presley Ball, circa 1870, at $125,000—Ball was one of the first Black photographers in America, learning his trade in Boston, launching his own itinerant studio in 1845, settling in Cincinnati from 1849 through the early 1870s, and then running studios in a succession of several southern and western towns until his death in Hawaii in 1904. Also of note was a 1949 edition of The Negro Motorist Green Book, which earned an auction record for any Green Book at $50,000.

Works by William Shakespeare drew strong interest from collectors in the May 4 auction. King Lear; Othello; and Anthony & Cleopatra, extracted from the first folio, London, 1623, sold for $185,000; a first edition of D’Avenant’s adaptation of The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, London, 1676, earned $42,500; and a first edition of The Two Noble Kinsmen: Presented at the Blackfriers by the Kings Maiesties servants, with great applause, London, 1634, brought $81,250.

Senior Specialist, Devon Eastland commented: “Speculation on the strength of collecting markets for art and antiques is rampant, but Swann's most recent Early Printed Books sales, teeming with English literary highlights and rarities mainly from the Elizabethan era, remained very strong. The interest of hardcore collectors of fine books from the handpress period is abundantly evident, especially when the offerings include important books in excellent condition and almost unobtainable editions of titles world-renowned to obscure.”

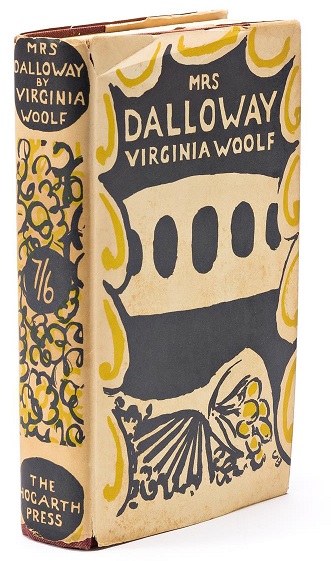

Additional season highlights included a first edition of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, London, 1925, in the rare dust jacket entirely unrestored ($30,000); a first American edition in the first state binding of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick; or the Whale, New York, 1851 ($27,500); and …more

Potter & Potter's Fine Books & Manuscripts Sale Realizes $628,000

Potter & Potter Auctions announced the results of their early summer Fine Books & Manuscripts sale held on June 1st, 2023. It featured 510 lots, had a 97% sell through rate and all prices noted include the company's 20% buyer's premium.

Potter & Potter Auctions announced the results of their early summer Fine Books & Manuscripts sale held on June 1st, 2023. It featured 510 lots, had a 97% sell through rate and all prices noted include the company's 20% buyer's premium.

Of the fine selection of groundbreaking first editions, Charles Dickens' Great Expectations, was estimated at $8,000-12,000 and sold for $24,000. The first edition, first issue copy was printed in London by [C. Whiting for] Chapman and Hall in 1861, and was among the earliest printings of its type, given its well documented errors and layout.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft's The Outsider and Others, was estimated at $4,000-6,000 and made $11,400. This first edition of the first book published at Arkham House in 1939 retained its rare and original dust jacket, and was one of only 1,268 copies printed by the publisher of weird fiction and horror.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois' (1868-1963) The Souls of Black Folk, estimated at $3,000-5,000, realized $14,400. This first edition was published in Chicago by A.C. McClurg & Co., in 1903 and was a very fine example of Du Bois’s most famous work, which remains a landmark in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African American literature to this day.

Henry Roth's Call It Sleep, was estimated at $3,000-5,000 and fetched $9,000. This copy of the first edition of the author’s first book was published in New York by Robert O. Ballou in 1934, included its rare first issue dust jacket, and was from the personal library of Larry McMurtry.

Thomas Hardy's The Trumpet-Major. A Tale, was estimated at $2,000-3,000 and brought $11,400. This first edition in book form was printed in London by Smith, Elder & Co. in 1880. This example in its rare secondary binding was originally published as a serial in Good Words magazine that same year.

Heinrich Klüver's Mescal: The ‘Divine’ Plant and its Psychological Effects, was estimated at $250-350 and sold for $2,880. Published in London by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. in 1928, this first edition was inscribed by Klüver and was the first work in English to study the psychoactive compounds of mescal. The lot also included a group materials related to Klüver including a booklet inscribed by Dr. Ronald Siegel.

Alice B. Toklas' The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book, was estimated at $1,000-2,000 and sold for $12,000. Published in New York by Harper & Brothers in 1954, This first American edition included her hand-written inscription of her famous “haschisch fudge” recipe. The lot included …more

by John C. HuckansOn Political Realignment (or Fear and Loathing inside the Beltway)

(originally published March 17, 2017)

The U.S. Election of 2016 was a game-changer for all sorts of reasons. To say the populist revolt came as a surprise to party regulars across the political spectrum is an obvious understatement, but the resulting emotional meltdown by people still in shock over the shifting loyalty and unexpected response of traditional working class voters (many of whom had supported Democrats since the Great Depression of the 1930s), only shows that it pays to do your homework. People who follow this column will recall that in July of 2016 we explained some of the reasons why Trump would perform bigly¹ in the 2016 general election. What follows is some observation and analysis that may contribute towards an understanding of recent trends. Or maybe not.

Party labels are just that – labels and nothing more. People who make a living seeking and trying to hold on to public office sometimes learn, to their annoyance, that …more

PBA's Sci/Fi, Fantasy, Horror Auction totals $500,000

PBA Galleries (PBA), one of the largest and most successful specialty auction houses in the world, completed an auction of over 400 lots of fine science fiction, fantasy and horror on June 2nd. . The sale featured signed and inscribed copies of major works by Stephen King, Philip K. Dick, Isaac Asimov, Octavia Butler, Frank Herbert, Ray Bradbury, Robert Heinlein, and many others.

The auction consisted of mostly signed first editions in exceptional condition. The wonderful examples in original dust jackets were from a single collection with many books rarely seen signed. Several new auction records were achieved during the sale, and when the hammer fell on the final lot, bidding had exceeded the highest estimate.

Samples of high performers include Dune by Herbert Frank ($22,500), The Dark Tower series by Stephen King ($22,500), The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula K. Le Guin ($10,000), Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert A. Heinlein ($11,250), The Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov ($15,000), and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick …more

Results of Hindman's May 11th Books & Manuscripts Sale

First editions of each of Jane Austen’s major novels led Hindman’s May 11th Fine Printed Books & Manuscripts auction. The five books, including Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility, realized more than $300,000. Overall, the sale brought more than $1.1 million, with a 94 percent sell-through rate.

“The passion of private collectors for rare works of literature and first editions led to very competitive bidding on the Jane Austen novels,” commented Gretchen Hause, Hindman Vice President of Books & Manuscripts. “We are thrilled with the results, and to see that the market for literature, and particularly for literature written by women, continues to gain strength.”

Highlighting the five Jane Austen first editions was Pride & Prejudice, which sold for $107,100, more than double its high estimate. The work, written by Austen at the age of 21 and finally published 15 years later in a small edition of approximately 1500 copies, stands as one of the most enduring and beloved works of 19th century literature. Austen’s first novel Sense and Sensibility sold for …more

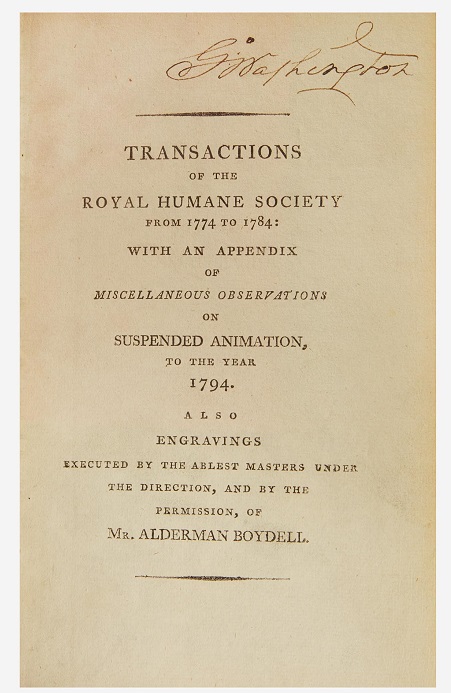

Some Results of Freeman's May 3rd Books & Manuscripts Sale

Freeman’s May 3 Books and Manuscripts auction was marked by fierce bidding competition over presidential material and significant Americana, resulting in the remarkable $441,000 sale of a volume from the personal library of George Washington.

“The market for presidential books, documents, and autographs is quite strong, and this exceptional result really drives that home,” says  Darren Winston, Head of Freeman’s Books and Manuscripts department. “As rare as material like this is, it’s still Freeman’s bread and butter, right in our wheelhouse, and we’re thrilled with the result—as is the consignor.”

Darren Winston, Head of Freeman’s Books and Manuscripts department. “As rare as material like this is, it’s still Freeman’s bread and butter, right in our wheelhouse, and we’re thrilled with the result—as is the consignor.”

The first edition of The Transactions of the Royal Humane Society was given to Washington during his second presidential term by physician Dr. John Coakley Lettsom, and features Washington’s bold signature at the top of the half-title page.

As books from Washington’s library seldom come to auction, this volume represented a very rare market appearance, with corresponding results: the title exceeded its pre-sale high estimate of $18,000 by more than 24 times following a spirited bidding war. Several other lots outperformed their estimates in Wednesday’s auction, including a fresh-to-market manuscript receipt for the delivery of John Dunlap’s just-printed Declaration of Independence, dated July 10, 1776, signed and inscribed by Owen Biddle (achieved $32,760; estimate: $3,000-5,000); an autograph letter signed by Thomas Jefferson (sold for $27,720; estimate: $15,000-25,000); and a 1787 land grant signed by Benjamin Franklin (achieved $17,640; estimate: $10,000-15,000).

A 1593 first edition of George Gifford’s A Dialogue Concerning Witches and Witchcraftes also outperformed estimates, achieving $17,640 (estimate: $3,000-5,000). Sixty-seven of the sale’s lots were from the Children’s and Illustrated Books Library of Nicholas Wedge, and together brought $105,556 against a pre-sale low estimate of $54,500.

Freeman’s next Books and Manuscripts auction, A Fine Collection of American Literature and History, will be held June 8. Freeman’s invites consignments of books and manuscripts year-round. For more information about consigning with Freeman’s, please contact Darren Winston (dwinston@freemansauction.com or 267.414.1247).

Swann's African Americana Sale

Swann Galleries’ annual Printed & Manuscript African Americana auction on March 30 was by a wide margin the most successful in its 28-year history. The sale set records with $1,377,463 in total sales and an even 94% sell-through rate. Eight lots hit the $50,000 mark—after only 14 lots having hit that mark in the previous 27 years combined.  It was the third-largest sale in the long history of the house’s book department, behind only two noted single-owner sales, the Epstein sale of 1992, and the Ford sale of 2012. All prices included the Buyer’s Premium

It was the third-largest sale in the long history of the house’s book department, behind only two noted single-owner sales, the Epstein sale of 1992, and the Ford sale of 2012. All prices included the Buyer’s Premium

The most notable feature of the auction was very strong bidding from institutional buyers. 43 different institutions were registered to bid in the auction. At least 105 lots were sold to 29 different institutions, in addition to numerous lots bought for institutions through private agents. “Numerous libraries, archives, and museums across the country are making up for lost time by increasing their representation of black history. For 25 years, Swann has been the leading conduit for bringing this source material from private hands into public hands,” noted Rick Stattler, director of books and manuscripts and specialist for the sale.

The top lot in the sale was an inscribed carte-de-visite by the important early photographer James Presley Ball, which brought $125,000. Only one other photograph of Ball is known to exist. A signed 1862 essay by the white abolitionist Portia Gage brought $8,000; it had been acquired from another auction house in 2003 for $345.

Items relating to slavery and abolition included an archive of letters from Richmond slave dealers, found an institutional home at $50,000, and the papers of abolitionist Theodore Bourne which included the minutes of the African Civilization Society reached …more

Outsider Artists Lead Hindman's Auction of Susan Craig Collection

Works by Roger Brown, Sister Gertrude Morgan, and William Dawson led Hindman’s single-owner auction of collector Susann Craig’s estate on March 9. A beloved figure in Chicago’s art world and a founder of Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, Craig left a strong legacy through her collection and passion for amplifying overlooked voices. The majority of works exceeded their estimates, with Chicago artists in particular seeing high-demand across the 325-lot sale.

Overall, the auction realized more than $551,000, well above the total estimate. A portion of the proceeds will benefit Intuit. “It was an absolute privilege to honor a woman who was so admired in Chicago,” commented Zack Wirsum, Director & Senior Specialist of Post-War & Contemporary Art. “Susann lived an incredibly rich life, and the success of the auction reflects her role as both a collector and a connector.”

Brown’s Crossing the Bandiagara Escarpment With Baobab Trees and Dogon Dancers, a very personal painting for Susann Craig, was the top lot of the auction, fetching $138,600 against a $60,000-80,000 estimate. 1989 was a pivotal year in the Chicago Imagist’s career, featuring his artistic responses to a range of subjects and issues.

The work was inspired by Brown’s 1988 trip to …more

Potter & Potter Auctions' Fine Books & Manuscripts Sale Exceeds $630,000

Potter & Potter Auctions' first book sale of 2023 (Thursday, February 16th) realized over $630,000 with a sell through rate of 95%. Prices noted below include the company's buyer's premium.

Books by, or with ties to Samuel L. Clemens ("Mark Twain", 1835–1910) performed well. A first edition, presentation copy of W.W. Jacobs' (British, 1863-1943) Salthaven inscribed to and by Twain, was the top lot in the sale. It was estimated at $25,000-35,000 and fetched $31,250. It was published by Methuen & Co. in London in 1908. In addition, Twain inscribed on the half title “It’s a delightful book. Mark." Below, Twain further reaffirms this statement, apparently in passing the book to someone else: “Bog House, Bermuda, March/10. I have read it about 5 times. The above verdict stands."

A 37 volume collection of The Works of Mark Twain published in New York by Gabriel Wells between 192 and 1925, was estimated at $6,000-8,000 and made $11,875. The limited edition set, number 79 of 1024 copies of the “Definitive Edition”, was signed by Twain on the front flyleaf of volume I. All volumes retained their original dust jackets. A 25 volume collection of Mark Twain's Works published in Hartford by the American Publishing Company between 1899–1907, was estimated at $8,000-12,000 and achieved $16,250. This set, number 233 of 512 copies of the “Autograph Edition” for subscribers - was published on india paper designed by Tiffany & Co. and etched by W.H.W. Bicknell. It also featured numerous engravings, 18 of which were signed by their respective artist. This collection is considered the rarest and most desirable of all the Twain sets according to experts. A first edition of Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner's The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, was estimated at $6,000-8,000 and fetched $16,250. It was printed in Hartford and Chicago by the American Publishing Company; F.G. Gilman & Co., in 1873. Also, two manuscript pages by Twain and Dudley were inserted in the copy. The first was in Twain’s hand and numbered 166 at the top; the other leaf was in Dudley’s hand and numbered 1446 at the top.

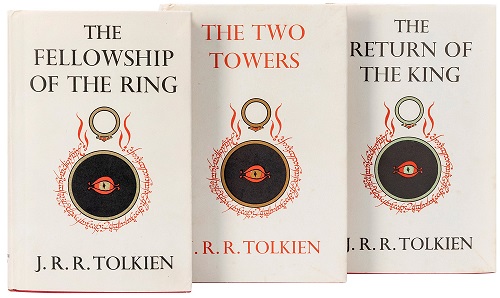

This sale featured remarkable first editions of some of the noteworthy books of the past two centuries. J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord Of The Rings trilogy,  estimated at $10,000-15,000, sold for $19,200. This trilogy included The Fellowship Of The Ring (1954), The Two Towers (1954) and The Return Of The King (1955). All were published in London by Allen & Unwin Ltd. and the provenance included the bookseller, R.S. Heath Ltd.

estimated at $10,000-15,000, sold for $19,200. This trilogy included The Fellowship Of The Ring (1954), The Two Towers (1954) and The Return Of The King (1955). All were published in London by Allen & Unwin Ltd. and the provenance included the bookseller, R.S. Heath Ltd.

Richard Nixon's (1913–1994) Real Peace: Strategy for the West, was estimated at $250-350 and realized $2,375. Privately printed in New York in 1983 this advance copy and galley proof was a first edition and one of 1000 copies of the private edition printed before publication. It included a TLS from Nixon to Martin Hayden which stated, “In view of the current national debate on foreign policy issues, I thought you might like to have a copy of the page proofs of a book on Soviet–American relations which I have just completed… I am publishing and distributing the book privately…to a selected number of government officials and opinion leaders in the United States and abroad who have expressed a serious interest in …more

by John C. HuckansEnd of the Road for a College

The village in which I live (Cazenovia in central New York) has a college, which traces its roots to 1824, that is about to close at end of the current semester. For most of its life it was a secondary school or seminary run by the Methodist Church. At some point it cut its religious ties and became a two-year college for young women. The first time it closed was in May of 1974 - I remember it well because we heard the news on the radio as we were driving down I-81, having just returned from a year in Spain (Granada) by way of the Stefan Batory, sailing from London to Montreal.