Books and Bookselling in Cuba

(originally published on June 26, 2011)

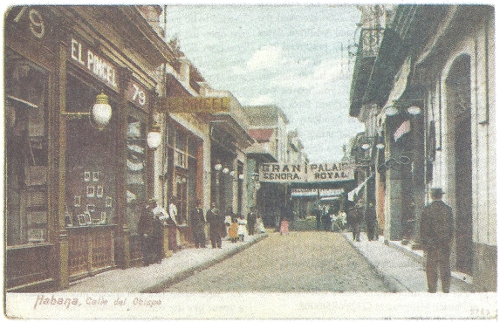

One of the things I regret in my exile from Cuba is that I never got to see any of the wonderful little bookstores along Havana's twin bookseller rows of O'Reilly and Obispo Streets. As a nine-year old the experience would perhaps have been lost on me, but I would certainly recall it as the bibliophile I am today. I have a rare postcard photograph of Obispo Street as it appeared in the 1920s (see below), and in that narrow thoroughfare of glass-fronted stores I think I can make out one of these mysterious shops, though the overhanging placards – which throw large shadows over the street and give it the air of a Moorish bazaar – are unreadable in the evanescent light.

Along this street in 1940 the writer Thomas Merton hunted for books before his conversion to monasticism. In his diary he writes that he saw a secondhand bookstore and walked in, “asking not for St. John of the Cross, but for philosophy books.” There weren’t any, so he walked a little further, and the next store did have a couple of shelves of philosophy: “I had to climb a ladder to look at them. I shouldn't have been surprised to be confronted first of all by none other than Nietzche.” For the most part, he says, the shelves were full of Spanish and French nineteenth century liberals and radicals.

This would have been a treat to me, as these writers helped influence Jose Marti and his independence movement.

“The next place I went to,” Merton continues, “was Casa Belga, with its big stock of French and English books, and its specialty in pornography and little editions printed in Paris... Henry Miller, Rimbaud's A Season in Hell...and then things like the Philosophy of Nudism. The idea of a philosophy of nudism gave me a laugh somewhat in a quiet, scholarly way...”

Merton entices even while insulting my sense of Cuban identity (“I had forgotten that Cubans and other Latin Americans are suckers for all kinds of sex books” – as if we had cornered the market on pornography). He next describes a bookstore that looked like a bank and didn’t even have books on display on the counters: “Every book in the place was expensively bound and was locked in behind wired doors.”

Merton entices even while insulting my sense of Cuban identity (“I had forgotten that Cubans and other Latin Americans are suckers for all kinds of sex books” – as if we had cornered the market on pornography). He next describes a bookstore that looked like a bank and didn’t even have books on display on the counters: “Every book in the place was expensively bound and was locked in behind wired doors.”

He continues: “I had given up hunting for St. John of the Cross and was going up the street when I saw a huge place with a great big sign saying La Moderna Poesia (Modern Poetry) which rather astonished me: what a huge shiny bookstore it was. Only when I looked into the window I saw a lot of straw hats...It turns out La Moderna Poesia was a department store.”

Merton is silent after that, so we do not know whether he found St. John in La Moderna Poesia. But in 1984 I had the good fortune to find myself on vacation in Miami, and there on Calle Ocho I discovered the exiled descendant of La Moderna Poesia – another “huge shiny store” but without straw hats in its window. It was very well stocked with both old and new books, as its ancestor must have been.

This diary is one of the scanty sources I have been able to track down for material on the history of books and bookselling in Cuba. My interest parallels the growing interest in Cubana which has made such books extremely scarce and expensive. Among my treasures is Havana: The Portrait of a City, by the 1940s black novelist W. Adolphe Roberts, which contains a chapter on books.

For the record, Roberts identifies the bookstores Merton visited in Havana's booksellers' row as La Moderna Poesia, Swan, and Libreria Cervantes on Obispo, and Casa Belga, Libreria Marti and Libreria Economica on O'Reilly.

Roberts tells us that in Havana of the 1940s large numbers of books were on sale at high prices, the few that were printed locally being relatively the most expensive. “Even secondhand books are dear.” Cuba, he adds, has no book publishers in the proper sense, only printeries which turn out jobs for cash or on terms. This is not surprising in a country beset by three revolutions in almost as many generations; what is a source of pride to me and other Cubans is that quality book publishing has survived through it all, as Roberts records. “Cuba has offered prizes for the best biographies of Jose Marti and other leaders, has issued the works, and has also put out a handsome India paper edition of the complete works of Marti. National annals, assembled by the Academy of History and other agencies, are lavishly preserved in print by the state.”

Evidently there are bibliophilic treasures awaiting the collector of Cubana who, like me, bides his time till the passing of the present regime renders worthwhile a bookhunting expedition to Cuba. This is not the case now, as the government understandably prohibits the exportation of antiquarian and out-of-print books, because of the high cost of paper and printing to replace scarce volumes. While I await that day, I content myself with books such as Printing in Colonial Spanish America (London, 1962), with its interesting chapter on the beginnings of printing in Cuba. There I discovered that printed books in Cuba date back to 1723, when Carlos Habre published Tarifa general de precios de medicina (General Tariff of Medicine Prices, reprinted in facsimile in 1936 by Manuel Beato in La primera obra impresa en Cuba). Important, non-commercial books began to be published in 1736 just after the University of Havana was founded, with the first being a university thesis, Coelestis astrea by Juan Urrea. The bibliophile with a taste for Cubana has nearly 300 years of collecting to catch up with.

To be sure, there were periods of artistic sterility. In 1777 Spain issued a royal cedula stating, “There shall be no printing house in the island, now and in the future, other than that of the Captaincy General.” Fortunately, this cedula was never fully enforced thanks to a succession of liberal governors.

In 1787 Esteban Jose de Bolona began an important tradition in Havana by publishing Ignacio de Urrutia Montoya's Teatro historico juridico, politico militar de la Isla Fernandina de Cuba. Though ceasing after the first fascicle, Urrutia's notes were used for his important Compendio de memorias, and Bolona thrived; he and his descendants were prominent printers in Havana till the mid-19th century, distinguished both for design and typographical excellence. They were Cuba's first world-class printers.

The 19th Century appears to have come short of the expectations engendered by the 18th, thanks to a succession of small-minded men determined to hang on to Spain's last American foothold by stifling intellectual activity. It was only with the greatest difficulty that Cuban patriots were able to communicate effectively with their countrymen, but Bolona had established a strong tradition that would inspire patriots both during the Ten Years' War and the 1895 Cuban War of Independence.

Spanish censorship and oppression, which helped to instigate Cuba's tradition of job printing, continued well into the 20th-century and was complained about by Roberts. Still, I noted that according to Cuba: Population, History, and Resources (1907) there were 1,817 printers on the island that year, certainly a huge resource for budding writers. This is a far cry from the Cuba of Fidel Castro, where according to visiting Christian Science Monitor journalist Mohammed Rauf (in his 1964 book Cuban Journal), printing is done entirely by the government, in a country where there are no private printing companies or publications. Of course, by 1964 all the bookshops were also nationalized, according to Rauf.

Many outstanding books were published in Cuba during the 19th-century, including works by internationally acclaimed poets Jose Maria de Heredia and Gertrudis Gomes de Avellaneda. Jose Marti, Cuba’s national poet and martyr in the War of Independence, had much of his work printed while in exile, but many important non-revolutionary works of literature, philosophy, poetry, history, and travel were produced by Cuba's job printers. Ironically, after Cuba won independence there were no literary giants comparable to those of the colonial period to help fuel the resultant explosion in publishing. According to William J. Clark in Commercial Cuba, there were twenty-three booksellers and fourteen printing offices in Havana alone as of 1898, but Cuba’s next internationally-renowned writer did not appear until the 1930s, giving some truth to the old adage that art thrives in adversity.

Cuban poets and writers suffered exile even in Cuba itself, under the oppression of both Spanish and Communist censors, beginning from the time of the new spirit of nationalism that arose during the Spanish occupation. Octavio Armand, an exiled poet who wrote in the 1970s, believed that “Cuban literature has actually been a long preparation for our exile.” “Look at the nineteenth century,” he said in an interview. “There is the poet Manuel de Zequeira, a surrealist avant la lettre. As a symptom of his madness and sense of isolation, he thought that when he put on his hat, he disappeared. The poet Napoles Fajardo provides an even more extreme (example)... one day he left Santiago de Cuba and was never heard of again…”

It was not until the 1930s, when Alejo Carpentier achieved worldwide recognition as the initiator of “magical realism” (in his The Lost Steps), and Nicolas Guillen's poems were translated into English by Langston Hughes, that Cuban letters again approached the heights of the previous century. And again we had a period of upheaval and revolution, with the Great Depression contributing to the new wave of adversity-influenced creativity.

Throughout this turbulent period, Cuban bookstores played a major part in promoting and preserving a national literature, and in relieving some of the harsh conditions facing native writers identified by Roberts. Some of them doubled as publishers in the tradition of 19th-century European and American booksellers. In a large collection of pre-1959 books that I was able to gather over a period of 30 years I have a treasured book, the happy surprise of an evening’s browsing at O’Gara’s Bookstore in Chicago in the late 1970s. The title is Poesias de Jose Marti, with a biographical introduction and notes by the noted Cuban scholar Juan Marinello, for this edition, that was published in hardcover by La Moderna Poesia and Libreria Cervantes (jointly) in 1928. This was part of a series called Coleccion de Libros Cubanos the aim of which was to preserve scarce classic works of Cuban literature, history and science that were only obtainable in the rare book market. The list of titles advertised in the back includes Ramon de Palma’s Cuentos Cubanos (Cuban Tales), Buenaventura Ferrer’s Viaje a Cuba en 1798 (Travel to Cuba in 1798), and my most sought-after title, Jose de la Luz y Caballero’s Como Educador (As an Educator), in which the great teacher first called for the founding of a Cuban Atheneum, urging friends who traveled to Europe to bring back books, books, and more books “for our Atheneum.”

It’s not easy to find such books anywhere, and especially in Cuba, where the heat and humidity have played havoc with the fragile paper commonly used by cost-conscious bookseller/publishers (publications of the University of Havana, the Academy of Cuban History, and the Ministry of Public Education were printed on better paper, and survive in greater quantity). My own searches have spanned thirty years, during which time I’ve browsed, scavenged, dug out and bartered for a collection now numbering barely 100 Cuban imprints, along with over 400 other books published here and elsewhere before 1959. An excellent source has been Libros Latinos of San Francisco, whose catalogues I’ve studied carefully for decades. Established in 1973, it is the leading purveyor of books and journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, maintaining a stock of over 25,000 titles on a variety of subjects. The owners travel year-round throughout Latin America to purchase new, rare, used and antiquarian books for their large clientele and back order list. Other sources have included local used bookshops, antique malls, antique stores, flea markets, eBay, and the occasional estate sale. Strangely enough, garage sales and thrift stores in the Cuban-American communities of Chicago, such as Logan Square and Lakeview, have yet to yield a single item.

Having maintained a lengthy correspondence with several relatives living in Havana, it naturally occurred to me to ask them to find books for my collection. This proved impossible on many levels: until recently the exporting of books was strictly prohibited by the Castro government. Then, too, copies of older imprints were difficult to find even in the book-rich flea markets of Havana, the Cuban equivalents of London’s old Farringdon Road bookstalls, and whenever found proved to be very expensive. My only success was when a friend of my stepfather visited Cuba and was able to purchase and bring back, by way of Colombia, a very rubbed and nicked but surprisingly crisp copy of Cuban national historian Ramiro Guerra y Sanchez’s La guerra de los 10 años (The Ten-Years’ War), two volumes bound in wraps. This was the 1972 printing of an important work first published in 1950 about the first Cuban war of independence (1868-1878) that failed but which laid the foundation for the successful one of 1895-1898. The covers are reinforced with transparent packing tape, indicating that the books had been read repeatedly. My stepfather’s friend found these treasures in the aforementioned Havana flea market and to this day refuses to tell how much they cost.

In The Blue Guide to Cuba of 1947, that I dug out of an ephemera drawer in an antique mall, I discovered a section on Cuban bookstores and newsstands. The opening paragraph should be of interest to Cuban historians, and I quote it here in full: “Generally considered as one of the leading cultural centers of the New World, Havana has several important book stores, and many foreign visitors have expressed amazement when they discovered that they could find the most sought for books in these... institutions of learning, comparable only in the world’s largest capitals.”

In 1952 Cuba celebrated the centenary of Jose Marti’s birth by engraving his likeness on the coins for that year. It also saw the opening of Libreria Marti at Presidente Zayas 413. An ad appeared in the Blue Guide of 1952 advising readers that “We specialize in old and modern Cuban works” – inviting them to ask for the bookshop’s catalogue. Pre-1959 Cuban ephemera is much sought-after today, especially magazines and catalogues, some of which occasionally turn up on eBay at surprisingly high prices.

For the record, the Blue Guide to Cuba of 1947 lists the most important bookstores of Havana, with their addresses in the Cuban style of including the street name first. Judging from information in the website Cuba Hostels, all except Cervantes have disappeared, caused no doubt by the nationalization of industries and censorship during the early days of the Castro Revolution.

Happily, Mohammed Rauf (see above) also pointed out that he walked into several secondhand bookshops that had not been purged. He also notes that old books are also available in the small bookstalls outside Havana, and, I might add, in Cuban homes , judging from the many interior photographs I have seen in travel books. More recently the Cuban émigré novelist Achy Obejas, currently living in Chicago, has gone on record as saying that her books are now being published in Cuba and sold in bookstores, a sign that the government has relaxed its censorship. According to an interview in the blog Literary Chicago, Obejas is now being described in Cuba as a Cuban writer – not Cuban-American. “For me, there was kind of a perverse pride in that,” she said. Consequently, and because I know well the love of books shared by many of my countrymen, I have faith that when “next year in Cuba” comes, passionate Cubana collectors and bibliophiles will return in force to truly happy book-hunting grounds.

Carlos Martinez runs Bibliodisia Books, an out-of-print and rare online bookstore in Chicago. Born in Havana and since 1976 a naturalized citizen of the U.S., he is a member of the Midwest Antiquarian Booksellers Association, and has written on books-related topics for The Caxtonian (magazine of The Caxton Club), Book Season, Ashland Life, Substance, and other periodicals. A shorter, slightly different version of the above article was featured on the ABE website.